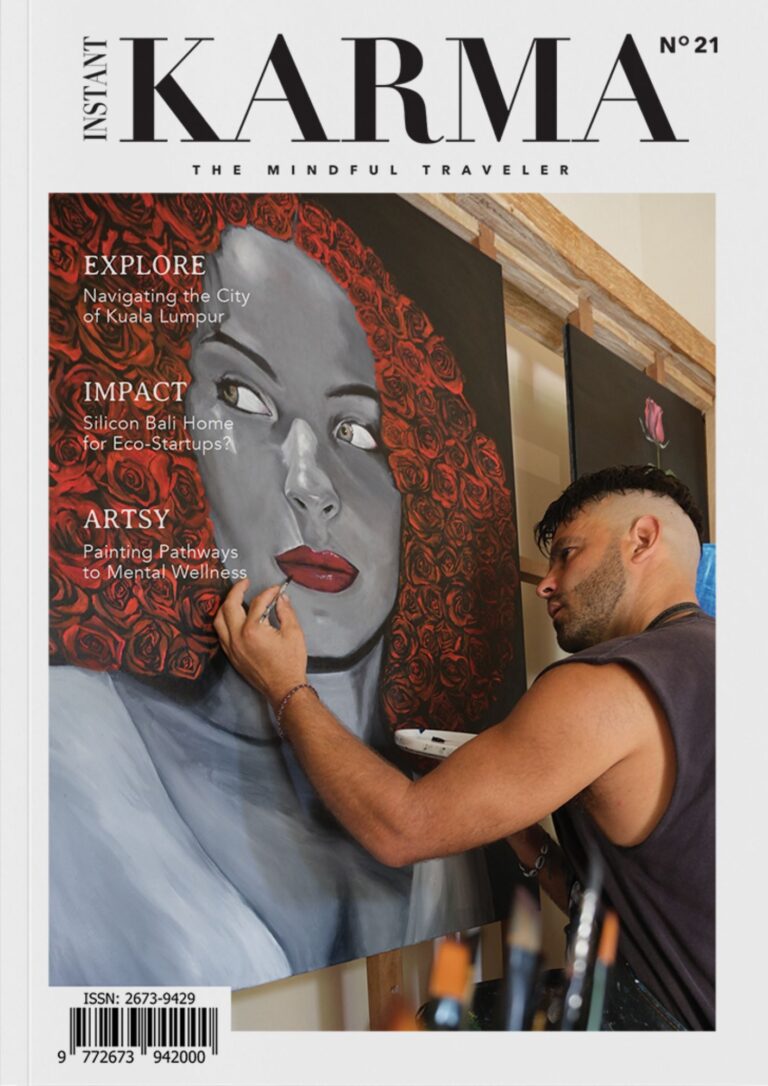

AS THE ISLAND RECOVERS FROM A PANDEMIC-INDUCED SLUMP, IT IS TRYING TO DIVERSIFY ITS ECONOMY BEYOND TOURISM AND ATTRACT GREEN BUSINESS. BUT CAN ECO-STARTUPS SCALE OR IS BALI MORE BEACH THAN BUSINESS?

The lifting of Covid-19 restrictions in June 2023 brought a tsunami of visitors back to Bali, Indonesia’s “island of the Gods”.

Many of the more than 4 million foreign visitors to Bali in 2023 were “Bule” surfers headed for Kuta to get sunburnt, guzzle Bintang beer and fall off motorbikes. But some were sustainability entrepreneurs looking to use one of the world’s most beautiful places as a base to pursue their purpose.

Though immigration rules have tightened – probably in response to a rise in crime and misbehaving foreigners – the island issued 70,000 foreign resident visas in 2022, taking Bali’s population of long- staying non-locals to over 100,000. Many Indonesian entrepreneurs have also relocated from Jakarta to Bali, escaping the air pollution, even-worse traffic and high costs of the capital for Bali’s startup hotspots of Canggu and Ubud.

The pandemic was a “big pivot” for Bali, says Lauren Blasco of AC Ventures, a Bali-based early-stage technology venture fund. Blasco, who is head of environment, social and governance (ESG) at the venture capital firm, adds that entrepreneurs who would otherwise set up in Singapore or Jakarta chose Bali, plugging into the island’s half-decent wi-fi and well-equipped co-working spaces.

The tropical paradise is starting to earn the “Silicon Bali” nickname it was given about a decade ago, says Nicolo Castiglione, an Italian entrepreneur who launched impact-focused angel accelerator Bali Investment Club in 2020.

INSPIRATORS AND ASPIRATORS

From hard-nosed investors looking to turn a fast buck from Indonesia’s multi-billion dollar sustainable business opportunity to “woo-woo” fly-by-nighters dabbling in alternative healing and spiritual psycho-babble, Bali is home to a colourful concoction of green startups of all sizes and shades of credibility. “It’s a crazy spectrum,” says Christian Oechtering, a German early-stage investor with an interest in sustainability, wellness, hospitality and psychedelics. “One minute you’re talking to a Russian billionaire building an eco-village, the next a former Amsterdam drug dealer turned life coach.”

There are two types of eco-preneurs in Bali: “inspirators” and “aspirators”, says Oechtering. Inspirators are switched on entrepreneurs looking to make a genuine difference, aspirators are less credible dreamers living in a bubble – and aspirators outnumber inspirators by two to one in Bali, reckons Oechtering. “You have to be careful who you work with. You don’t want to squander your time here,” he says.

A NATURAL HOME FOR ECO-STARTUPS?

Bali is a natural launchpad for conscious startups because of its unique cultural identity, says Blasco. Rooted in the island’s philosophy is the saying Nangun Sat Kerthi Loka Bali, which roughly translates to respecting nature and culture to make Bali prosperous. In that sense, new enterprises that work on conserving the island’s natural beauty have a head start, says Toshihiro Nakamura, a former United Nations executive who co-founded Kopernik, an Ubud-based research and development lab for startups working on social and environmental problems.

It helps that the government wants to diversify Bali’s economy beyond tourism. Haunted by the lean pandemic years of empty hotels and barren beaches, when Bali’s economy was hit harder than any province in Indonesia, the authorities want to attract greener industries and reduce the island’s reliance on tourism, which accounts for 60 to 80 per cent of the local economy.

Under the Kerthi (which means fame and glory in Sanskrit) Economic Roadmap set in 2021, regulations were introduced to boost renewables, electric vehicles and energy efficiency, and build a clean energy ecosystem around Bali’s 2045 net-zero target, Indonesia’s most ambitious provincial decarbonization goal – 15 years ahead of the national 2060 net-zero target.

Bali is Indonesia’s “net-zero emissions laboratory” and could provide a blueprint for the country’s energy and transport systems, says Sofwan Hakim, senior lead, Bali Programme Management Unit, at non-profit World Resources Institute (WRI) Indonesia. Bali, though still powered by a coal-based grid, can pilot low-carbon solutions and develop infrastructure that can be scaled and adopted across Indonesia, he says.

There were promising signs that Bali’s net-zero regulations would bear fruit after the G20 Summit in November 2022. In that month, a 100 kilowatt-peak floating solar power plant was launched in Nusa Dua, the upmarket southern tip of Bali where the top luxury hotels hosted visiting G20 dignatories, and the streets were suddenly whirring with electric vehicles (EVs).

But many of the EVs on Bali’s streets for the G20 have returned to Jakarta and the Waduk Muara Nusa Dua floating solar plant, which was billed by an executive from national energy utility PLN as “not merely a showcase for the G20”, is reportedly not operational.

Industry-watchers say that Bali’s clean energy regulations, while progressive compared to other Indonesian provinces, have been slow to fulfil their promise. Rayhan Alghifari, policy and advocacy associate at New Energy Nexus, a non-profit that supports clean energy entrepreneurs, notes that there is a lack of follow-up programmes to help clean energy entrepreneurs access incentives, such as tax breaks for converting fossil fuel-based vehicles to EVs and EV charging.

He adds that there is also a lack of technical regulation and incentives to develop solar rooftop power plants on the island, and even a surprising lack of regulation or incentives for sustainable tourism.

BALI’S ECO STARTUP SPECTRUM

Though there are no major businesses or government offices in Bali, the island is home to some of Asia’s most well established names in sustainable development, mixed in with a new breed of startups that has popped up post-Covid. Kopernik has been around since 2013. Terratai, founded by former Wildlife Conservation Society executive Matthew Leggett, which aims to address a gap in the conservation finance ecosystem in Asia, emerged only last year.

Some are working to fix local problems, with waste being the most popular issue to fill the island’s infrastructure gap for a waste-heavy economy driven by tourism. Environmental group Sungai Watch, which instals river barriers to collect plastic waste before it can enter the ocean, is among the most notable non-profits, founded by Bali-raised French siblings Gary, Kelly and Sam Bencheghib in 2020.

Other waste-focused startups in Bali include the award-winning conservation group Bye Bye Plastic Bags. Founded by local sisters Melati and Isabel Wijsen in 2013, their campaigning led to a ban on plastic bags, styrofoam containers and single-use plastic straws in Bali in 2019.

The tourism industry consumes a lot of water, with the hospitality sector depriving nearby communities of a reliable water supply. Startups such as Bali Rain, which produces water products from rain water, and Terrawater, a social enterprise which sells ceramic water filters, are working to ease Bali’s water crisis.

Meanwhile, Green School, Asia’s first eco-centric school founded in 2008 by American entrepreneurs Cynthia and John Hardy, is birthing a new wave of Bali eco-preneurs. Seventeen -year- old Freddie Hedegaard started carbon project verification firm Dungbeetle while still at school, supported by Luke Janssen, an entrepreneur who founded Singapore-based mobile technology firm Tiger Spike.

FUNDING GAP

While its startup ecosystem has grown rapidly since the pandemic, Bali cannot compete with Jakarta or Singapore in one important way: access to capital. As such, although there are countless sustainability-related businesses in Bali, most are small.

Indosole, which makes shoes from recycled tyres, is one of the few to have gone global, says Castiglione of Bali Investment Club, whose company helped to fund the venture. Blasco says that while capital might not be on Bali’s doorstep, with so many people coming in and out, the “Island of the Gods” offers plentiful opportunities to meet the right partners or find the next hire. Plus living and working and Bali is considerably cheaper than Singapore or Jakarta, which helps to keep costs low.

But while Bali is an ideal place for pioneering entrepreneurs to be “creative and scrappy”, the island needs more big companies based on the island to raise its profile, Janssen adds. “Bali needs a Gojek,” he says.